The basement of Belgrade’s G Hostel was dingy, cold, and walled by cement and rough plaster. The beer pong table was lit up with lasers and black lights. We passed it and found a room the size of a solitary confinement cell, maybe six feet by 10, where on ratty futons sprawled two sunken-eyed boys and three chirpy blonde girls with heavy makeup.

We sat with our beers opposite them. M, a Serbian friend, leaned in to me. “This is not Serbia,” she uttered. “I don’t know what the fuck this is.”

The girls were American, the boys Romanian. F’s eyes lit up at the news. “Oh! Neighbors!” she exclaimed, throwing her arms up. The sunken-eyed Romanians said nothing and stared at her. “Romanians don’t like us very much,” M informed me as F quietly sat back down.

The Romanians, it turned out, were here for a shot at the $7,000 prize of a DOTA 2 competition. DOTA 2 is a massive online video game so enormously popular that international competitions are held with cash prizes of up to a million dollars. While the shorter, wily-haired, quick-talking Romanian with fewer social skills than white teeth droned rapidly on about the strategy of the game, F and the bulkier, hunched-over Romanian and I escaped to the back courtyard, such as it was—a slim patch of concrete surrounded by towering Soviet apartment buildings, which was still, technically, outside.

Hunch turned out to be an okay guy. He was a part-time standup comic (apparently the money is great over there), part-time graphic t-shirt designer (a playboy bunny once wore one of his designs and posted the shot to Facebook; “That week I sold 100 shirts,” he claimed), part-time urban planning student (with dreams of opening a free arts space in Bucharest) and part-time video game enthusiast.

He apologized for his short drunk friend, enforcing how important it was for them to win this money. Times are hard in Bucharest. “We don’t have what you call community,” he said. “We have an expression—I will translate for you—‘I wish for your neighbor’s goat to die.’”

“Oh!” F said. “We have that expression, but with cow.”

F, an aspiring fashion designer, probed Hunch for info on the graphic t-shirt market. Hunch tried to explain how his business worked, which effectively involved making cheap shirts of poor quality and not giving a shit; he sort of petered off after that. “I’m sorry,” he said, leaning back. “I am drunk and tired and speak lousy English.”

As guests began filing out to bed, a calm Frenchman named Jean joined us. He had his country’s nose and a defeated smile, and was drunk in the way all lonely extroverts get when their friends stop listening; he monologued to us about his lousy airline PR job, his aimlessness, his lack of desire to ever perform a meaningful duty in his life. His friends barged outside; one grabbed Jean’s hair and began humping his face and laughing, then downed a small bottle of raki, yelled things in French and left. Jean looked at us apologetically. “I am sorry for my friend,” he said. “I really can’t stand him. He is just saying things about my sister. But never mind! Never mind… the bollocks. You know it? Ha, ha, ha…”

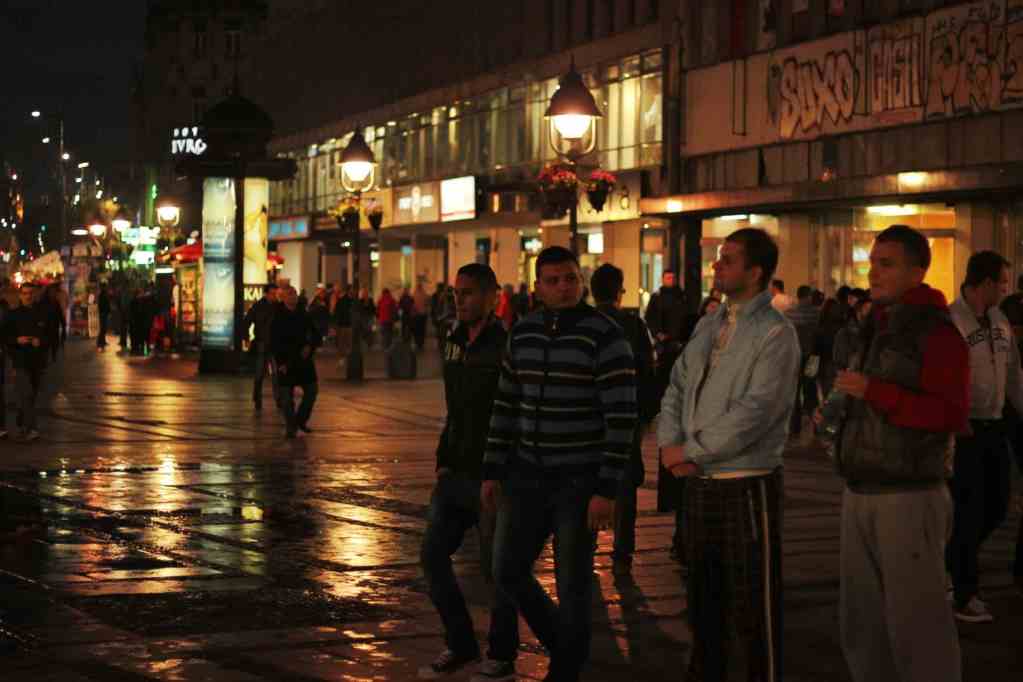

F grabbed her hostel employee friend and the three of us walked over Belgrade’s downtown hill to a harsh concrete apartment complex somewhere north for the birthday party of a musician friend of theirs. The apartment was too small to fit the hundred-odd long haired, scraggly bearded, lip-pierced souls hand-rolling cigarettes. Everyone wore brown or gray slacks, white or off-white shirts, cracked leather suspenders, woolen A-line skirts, bristly tweed jackets, black eyeliner, red lipstick and big, drunk smiles. The only light came from lamps, not overhead. It was J’s birthday, he who is the lead singer and acoustic guitarist of his Serbian folk band; he, who along with his accordionist and bongo player, played loud classic local folk songs everyone knew the words to, drinking homemade wine and greeting newcomers with a kiss on both cheeks.

This crowd was pleasantly different from the ragtag hostellers. These were proper Serbs, chatty and drunk, shocking me with their fluency not only in English but also self-deprecation. One dude came from Pirot, near the Bulgarian border. “You’ve never heard of it,” he said, solemnly. “And there’s no reason you should.” I asked a Herzegovinian friend what Serbian films were like, and he explained that most were depressing war dramas or dark comedies, with titles like Pretty Village, Pretty Flame; Death of a Man in the Balkans and Tears For Sale.

Serbia’s Gen-Yers have seen some heavy shit: the fall of Yugoslavian communism; the famine that resulted; the bombs NATO dropped years later; a subsequently ravished landlocked nation torn apart by racial differences; a modern country that, at best, falls under the slowly disappearing umbrella term of the “Second World”, plagued by high unemployment and weak currency. Many want to escape; few can. “There are no opportunities in Serbia,” the man from Pirot told me, openly envying how easily I could teach English in South Korea with no credentials but my native tongue.

All this misfortune has turned the best of these kids into black comic absurdists, Beckett caricatures so constantly defeated that all they can do to combat absolute depression is sing and drink and shout in the face of everything that’s wrong with the world. This they do very, very well.

Pingback: A Walk Around Belgrade Serbia