I had never sought out a grave before. It was a chilly October morning when I passed the wooden sign for Kearsarge Cemetery in North Conway, New Hampshire. I walked the damp, narrow paths, brushing snow from headstones in search of my grandmother’s name: Martha Anne Burke. After a half-hour, I turned toward the exit and texted my Mom that I had come up empty.

Talking to her from my dad’s house an hour before, I had asked where her mother had been buried a decade ago. She gave me vague directions, unable to remember the exact location. While we were talking, I heard a loud thwack. A bird had flown into a window beside me. It died instantly, the third one in as many weeks.

My dad’s chalet is his own monastery. It’s buried in the woods, tucked alongside a stream overlooking a pond. It’s the third house my dad, Greg, has built on the unpaved road in Eaton Village, NH, a picturesque town in the White Mountains with population of roughly 400 people. It’s his empty nest, now that my brother and I are grown and living in Boston, Massachusetts. He calls it Shangri-La, a charming place to lay his head, if you ignore the intermittent thuds of beaks hitting glass.

The first time I witnessed a bird’s fatal miscalculation, I was working on my laptop at the dining room table. I slid open the glass door and crept toward the stunned chickadee. The crown of its scalp was bloodied, eyes vacant. I watched the bird take its last puzzled breaths before its body went stiff. I buried it in the woods later that day.

I told my Mom about the bird that had just flown into the window.

“There’s an old wives’ tale about that,” she said, her voice shaky. “It means death is near.”

The timing was synchronous. I was about to visit a cemetery, and in a few weeks I was planning to ride my motorcycle from New Hampshire to Southern California, taking a 4,300-mile route through the deep south. I fancy myself a man of reason, not given to supernatural explanations for phenomena, but with a trip of such magnitude ahead of me, I could have done without the omen. My mom offered to visit the cemetery with me, but I insisted I go alone.

The graveyard was less than a mile from where my Grandmother had lived most of her life. I had spent summers there as a child, tinkering with tools in the backyard, among the rhythmic chirping of chickadees in the birch trees. Inside her house, I would sprawl out on the living room floor and send GI Joes on black-ops missions. Beside my play area was a cabinet full of decorative hummingbirds, which Anne collected. Every day, she would watch The Price is Right while making progress on a puzzle. In the afternoon, she would nap on the couch and “rest her eyes.” The visits were escapes from the vortex of divorce. She died when I was seventeen, freezing those summer days in mental stasis.

There are many reasons for visiting a grave. Since I was moving across the country, perhaps I was visiting her grave to say goodbye. Maybe I wanted to tie-up a loose end. I hoped it wasn’t just a project.

It was likely a result of my stay with my dad, who is acutely aware of the brevity of this ride we call life. During the six weeks I lived with him before I left for California, he discussed a fatal diagnosis or mortal accident nearly every day.

“An old teacher of yours was diagnosed with brain cancer,” he would inform me during a commercial break while we watched the news. “A friend of mine is fighting for his life after a motorcycle accident,” he might say before he left for a ride of his own.

Fixating on death is Greg’s way of illustrating his most cherished saying, cliché as it may be: life is short. Such insights usually come in the stillness of early morning, around 3 or 4 AM, as he plans his workday over coffee. As I slept in the spare bedroom, he would scribble reminders of life’s shortness on scrap paper. I thought of these notes as letters – morning prayers, affirmations for his oldest son.

Some of these letters concerned mundane tasks. “Pick up some eggs, please,” or “clean the stove after cooking.” “Leave no trace, dude” were his standing orders. But some letters offered deeper glimpses into his psyche, revealing thoughts we all share to a greater or lesser degree. “Most people don’t think they could die tomorrow,” one note said. “I don’t think that way. Don’t waste time. The world is your oyster.”

Each day I awoke to his letters. “The next door neighbor has cancer, won’t see the spring. Fifty-five-years-old. Life is silly short, dude.” Three weeks before I moved in, I was backpacking in China. Below a picture I had posted on Facebook of me hiking The Great Wall, my dad wrote his favorite saying: “Geologically speaking, a human life is only ten seconds long.”

An avid mountain biker, fierce downhill skier and healthy eater, my dad is the picture of health, but even at 59-years-old, he suspects he’s on borrowed time. When his father died at 55 and his uncle at 54, he began to think of the 50s as danger years. (It’s worth noting that on the day I was born, he attended the funeral of his best friend’s father.)

Greg also thinks about the end because his mother won’t stop talking about it. While I was staying in Eaton, in Santa Barbara, California his 77-year-old mother, Cheryl, was creating her living trust. Cheryl had made her son the executor and was inundating him with emails about his obligations upon her passing. He became overwhelmed. “I’ve just about had it with the emails,” he said, closing his laptop.

It made me realize that my Dad prefers to take a philosophical approach to death over his mother’s more practical one. He also refuses to plan for death, because he’s too busy getting the most out of life. Take a stroll around Shangri-La and life-affirming messages abound. Tacked to the walls or hanging in frames are postcards and pictures with inspirational quotes. A postcard in the downstairs bathroom has a mouse on the front wearing a helmet, inches from a block of cheese in a trap. Another quote hangs next to that, Hunter Thomson this time: “Life should not be a journey to the grave with the intention of arriving safely in a pretty and well-preserved body, but rather to skid in broadside in a cloud of smoke, thoroughly used up, totally worn out, and loudly proclaiming, ‘Wow! What a ride!’”

A self-employed contractor, Greg spends his days replacing roofs, building additions and custom homes. If you call him in the morning, he’ll shout that he’s “building America.” On the job site you’ll see a man always dissatisfied, eager for tangible measures of progress.

“We need a success,” he once told me, as we stared at the foundation of a garage without walls. After we built and then stood up the walls, his mood brightened. He sung the lyrics Tracy Chapman’s “Fast Car” playing on the local radio station. During the commercial break the station broadcasted its tagline – “93.5, music without boundaries” – to which he yelled, “No boundaries, baby!”

Greg’s workdays end at 3:30 PM, which justifies a 15-minute lunch. “Anything longer breaks momentum,” he claims. When he gets home, he might call a friend and ask, “Can you play today?” An hour later he’ll be peddling his mountain bike up a stump-riddled trail, his heart rate jacked, eyes glued to the forest floor. Or perhaps he and his girlfriend might take a leisurely motorcycle ride on the Kancamagus Highway, a 34-mile scenic highway that stretches from Conway to Lincoln.

A week before my transcontinental journey, my brother and I were talking about our dad as we walked the footpath around the Charles River in Boston. I pointed to a row of docks along the river.

“A year ago, I was having beers there with dad and his girlfriend. I asked him who he thought the wisest person in our hometown was.”

“What’d he say?” Daniel asked.

“He thought for a while, but didn’t have an answer.” I paused, watching a sailboat bob on the Charles. “Honestly, I think Dad could make the short list.”

At the time, I was reading Meditations by the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius who repeatedly reminds the reader that death is inevitable. “Despise not death, but welcome it, for nature wills it like all else,” writes Aurelius.

It sounded like my dad’s letters.

As we strolled, my brother and I pondered our father’s wisdom. We balanced the “wise” with the not-so-wise. He was impatient; he could be judgmental; empathy wasn’t his strong suit; and his temper was the stuff of legend. However, in spite of his impatience and intolerance, his lack of understanding and hotheadedness, he was a blue-collar mystic: Mount Washington Valley’s philosopher king.

Daniel made a shrewd point. “Dad knows what’s important.” Meaning, he didn’t just make it a priority to attend his kids’ sporting events, reward good grades, and ensure our path to college; he also continually reminded his boys that life is not to be wasted.

For 32 years, I had been on the receiving end of this wisdom, and yet I had spent the last several years restless and disillusioned in office settings. I once promised myself that I would never inhabit a cubicle, but broke that promise when I was promoted to the executive floor of a global company as a corporate communications writer.

On my first day in the new role, my boss walked me around the cubicle farm, passing offices for directors, vice presidents and C-level executives.

“Pick any cubicle you want,” she offered, as if it were a great honor to select a windowless box where I would stare at a screen for eight hours a day, five days a week.

“It looks like a prison,” I said.

She gave me a puzzled look (through experience, I learned not to speak in such ways among the institutionalized). At my next job, I had an office, but I still felt caged. Between meetings, I would gaze out my third-floor window into the busy square, my eyes flitting over pedestrians, like an eager puppy following hummingbirds at the feeder.

To decompress after work I would visit the gym for a spin class, where I would bounce up and down for an hour, synchronizing to mashups and remixes. Later, I would sprawl out on the couch and watch Charlie Rose tilt his head at newsmakers.

It’s difficult to complain, I suppose. I had a stimulating job in a stimulating city at a stimulating workplace, a Cambridge-based biomedical research institute, which some scientists likened to an artist’s colony. But I was decidedly overstimulated. Intellectually, I was pleased with the life I had built, but my body was just along for the ride – I was living from the neck up. I feared if I didn’t make a change, my body would rebel against my mind.

My dad and I were eating dinner at the kitchen table when I brought up what seemed like his favorite subject.

“Are you afraid of death?” I asked.

His face contorted into a confused, almost defensive expression. “No, Dustin, I’m not afraid of death.”

“Why do you talk about it so much?”

He took a sip of tequila. “I don’t know.”

I wondered if he was more afraid than average, but had never admitted it to himself. Unconsciously, I think we’re all scared of dying. We deny our own mortality, because the concept of nonexistence is too difficult to bear. We conduct our lives as if we are not destined for old age, illness and an inevitable death. We forget that nothing is permanent, including ourselves.

I think discussing death is my dad’s way of dealing with this existential dread. It might be a subconscious way of nourishing the notion of impermanence, keeping it close so he wouldn’t forget that nothing lasts. And, in doing so, it would propel him to live a richer, fuller life.

“I’m afraid of dying,” I admitted.

I didn’t have a clear answer as to why. A lifetime doesn’t seem like enough time. I’m convinced I won’t be able to say everything I need to say, learn everything I want to learn, do everything I hope to do.

“I’m also not sure if anything happens when the lights go out. Not yet, at least.”

I confessed that the apple hadn’t fallen far from the tree: I knew that life was appalling brief. But while I found my dad’s advice inspiring, I occasionally found it paralyzing. Working 9-5, I sometimes overwhelmed myself with the idea that I was misspending my days.

I told my dad, “It’s not always easy living in the shadow of your awareness of death.” I didn’t yet know how to design my life in accordance with his wisdom.

He told me that I would figure it out, but then rather callously fanned the flames of my angst. “I could never live like you and your brother: Living in the same city – any city, for that matter – working in the same building, and taking orders from a boss.”

He was particularly hostile toward the idea of waiting until retirement to satisfy one’s desires. Retirement planning was postponement, procrastination, a waste. And wasting time is a fate worse than death, in his eyes. No, that’s not quite right: it is death. If my

dad was feeling cooped up during a New England winter, he’d ship his motorcycle to Southern California and ride it down the Baja peninsula with his motorcycle buddies.

He was 22-years-old when he became self-employed as a general contractor. “I was on the porch with my father-in-law,” he told me. “He was a talented carpenter and always talked about starting his own business, but he never did. I decided that night I was going to work for myself.”

At the time, my dad had $1,500 in his checking account. I was two-years-old. Daniel was six-months-old. He didn’t have a driver’s license, so he rode a bicycle to his first job. After he got the job, he told my mom: “Well, I got it, now I just need to figure out how to do it.” He’s been in business for 30 years, figuring it out every day, he says.

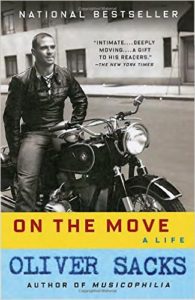

I felt as if I had spent several years ignoring the wisdom in my dad’s letters. Then I stumbled upon Oliver Sacks’ essay “My Own Life” published in the New York Times. The neurologist and author had learned he had terminal cancer. I was moved by Sacks’ humility and grace in the face of inevitable death.

My dad and his mother talked about death often, but Sacks was actually dying. “It is up to me now to choose how to live out the months that remain to me,” he wrote in his essay. “I have to live in the richest, deepest, most productive way I can.”

After reading his autobiography “On the Move,” I decided to quit my job and embark on a walkabout, a time to reflect on my own life and eventual death. My pilgrimage would have three acts: First, I would backpack through China for three weeks. Second: I would spend six weeks in my hometown. Third: I would spend a month driving my 1982 Honda Nighthawk across the country to California.

As I was planning my travels, I wrote Sacks a letter in which I thanked him for inspiring me to embark on an immense adventure. I wished him joy in his final days and the satisfaction of knowing that he had lived a rich and honest life.

Several months later, I was in a hostel in Guilin, China when I learned Sacks had passed away. It was at 3 AM, but I was awake, my stomach in a revolt from food poisoning. I had spent an hour clutching my abdomen, groaning and scrambling to and from the bathroom. I took an antibiotic and tried to distract myself with Facebook. As the pain began to fade, I saw the headline of Sacks’ passing.

As I was leaving Kearsarge Cemetery, my phone buzzed in my pocket. My aunt Stephanie had called to help me narrow the search for Anne’s gravestone to a small quadrant of the cemetery. I reentered the graveyard with renewed confidence. It took fifteen minutes before I saw a decorative red hummingbird beside my grandmother’s name on a gravestone.

I had arrived. But I still didn’t know why I had come. Perhaps I had visited the cemetery for the same reason my dad wrote his letters: by acknowledging death we make space for life.

I whispered an apology: for not visiting more during high school. I followed with a thank you: for the safety and predictability she had provided when I was a boy bouncing between parents. It’s rumored that she had nurtured my fondness for reading; I thanked her for that, too.

“A bird flew into a window at my dad’s house today,” I said. “According to superstition, it means death is near.”

Before I had left my dad’s house, I looked up the wives’ tale online, and discovered there was another, more comforting interpretation. It also means change is near.

As I stood over the gravestone, I remembered the letter I had read aloud at Anne’s funeral. My family huddled around me as I spoke; tears smacked the pages in my trembling hands. When I finished reading, my aunt told me that my grandmother had heard every word. If that were true, she could hear me now.

“Watch over me as I change, nanny,” I said. Then you can rest your eyes forever.”

* You can watch a video version of this essay at Outside Online.

Such a beautiful essay! Best wishes on your journey.

Fantastic piece, Dustin. Hope the trip breathes more life into your days!

Thanks for the brilliant and thoughtful essay, Dustin. Have an amazing trip!